The Petrov Factory cafeteria in Stalingrad, 1960

- The Left Chapter

- Aug 20, 2025

- 6 min read

From the Soviet Press in 1960, a look at the Petrov Factory cafeteria in Stalingrad (just before the city was renamed to Volgograd). Factory cafeterias were of major importance in the USSR where they served inexpensive and healthy food. (We have looked at this before in: Dinner at a Soviet factory cafeteria, 1963)

By Georgi Pavlov

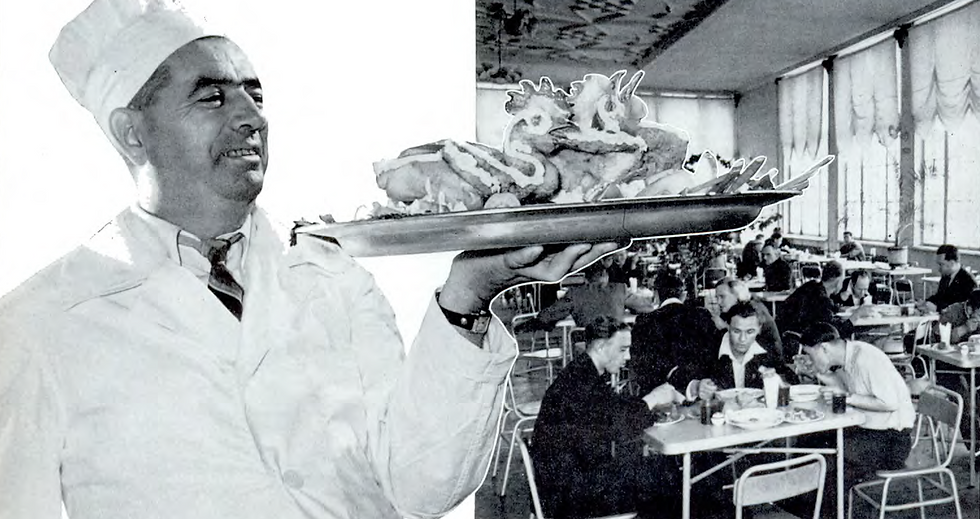

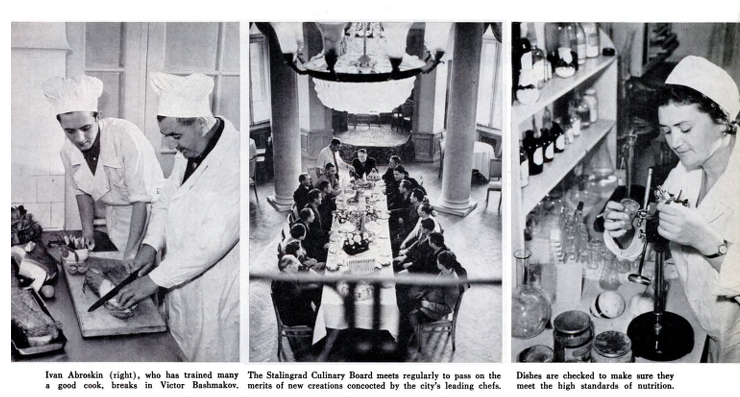

IVAN Abroskin is chef of at the Petrov factory in Stalingrad which manufactures farm machinery and oil equipment. The cafeteria is housed in a two story building on the plant grounds, and has two large dining halls and a gleaming modern tile and stainless steel kitchen. It's Abroskin's job to see that his 3,000 daily customers get up from the lunch and dinner tables well fed and pleased with the dishes he serves.

Usually you will find Abroskin -- he'll be pointed out to you as the stocky man with a snow white jacket and high chef's hat standing over the electric stove with his eye fixed on a simmering griddle. It's likely is be a new fish dish he's experimenting with -- Ivan is famous for his fish delicacies. When the dish is fried to the exact turn that meets his very demanding tastes he'll be glad to answer your question.

How he evolved into a cook? Abroskin says he has to to go back quite a stretch to answer that question. In 1928, when he was he came Stalingrad from his native village to learn a trade. He got a job at the construction site of a tractor plant land learned how to operate an excavator. But he very soon traded his excavator bucket for a cook's ladle.

"A Bushel of Salt"

"This is the way it happened," Ivan explains. "Evenings after work my friends and I used to cook our own suppers in our rooming house. We arranged it so that each of us was cook in turn. But the boys liked my cooking best, so they all insisted that I make supper every day. That's how I started cooking.

"Every once in a while I'd get a pointer from one of the real professionals and try it out on the boys. I liked cooking so much that I decided to change trades and got a job as a kitchen hand at a factory cafeteria. I was lucky enough to work under Vasili Chernikov, the head cook. He was fond of young people and used to gather all the kitchen hands like myself around him and teach us the fine points of the trade.

"I still remember his favorite expression. When we'd bombard him with questions—why do you do this and how do you do that—he'd stop and say: "Take it easy. Step by step. Don't be in such a hurry to swallow every recipe before you taste the salt in it. You'll have eaten a bushel of salt before you become a cook worth the name."

Abroskin ate his "bushel of salt" a long time ago. He celebrated his thirtieth year in the kitchen in 1958. It's no easy job meeting the tastes of so many different people, he'll tell you, but he likes the constant challenge and, say his customers, it's the very rare occasion when his dishes don't hit the spot.

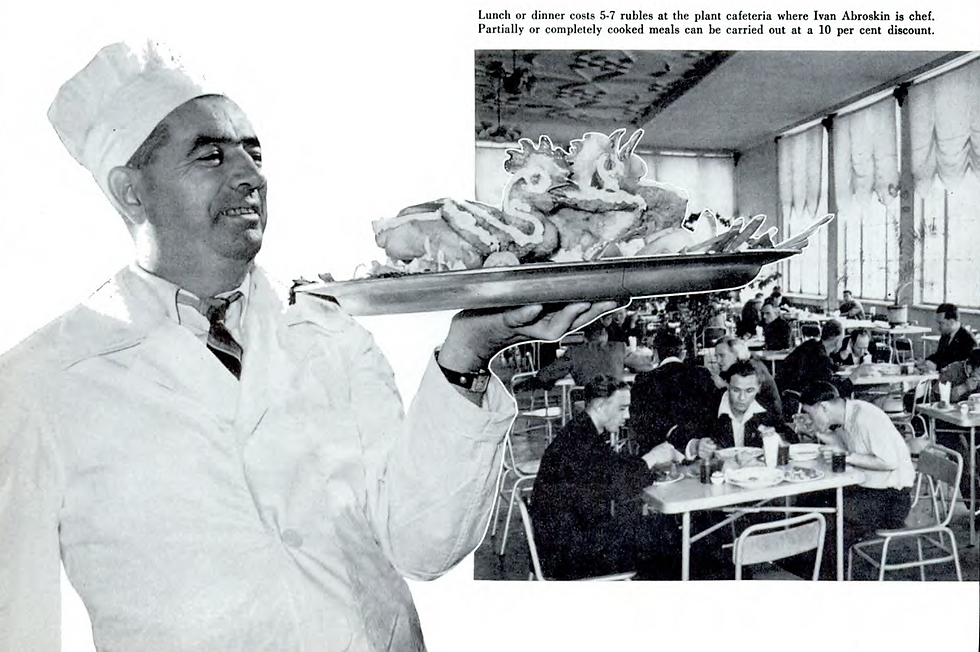

Ivan Abroskin has been collecting cook books for years and credits the hobby with his inspirations for new ideas.

Wartime Chef

Even during the war period, with rationing and shortages, Abroskin was famous for his imaginative touch with food. He worked in one of the kitchens that served the army during the heroic defense of Stalingrad. After that incredible battle which turned the tide of the war the city was a picture of desolation -- nothing but ruins, piles of broken brick and twisted steel surrounding the burned down skeletons of houses and factories. Practically every building in the city had to be rebuilt.

The cafeteria where Abroskin had worked was completely destroyed. At Beketovka on the outskirts of Stalingrad a small single-story building by some miracle had remained intact . "This is your cafeteria," the veteran chef was told.

He and the staff pitched in, built what was necessary, installed equipment and got started cooking for the people who were rehabilitating the city. It wasn't long before Stalingrad was back to normal with new stores and restaurants . Shortly afterward, Abroskin's cafeteria was moved to one of the new buildings.

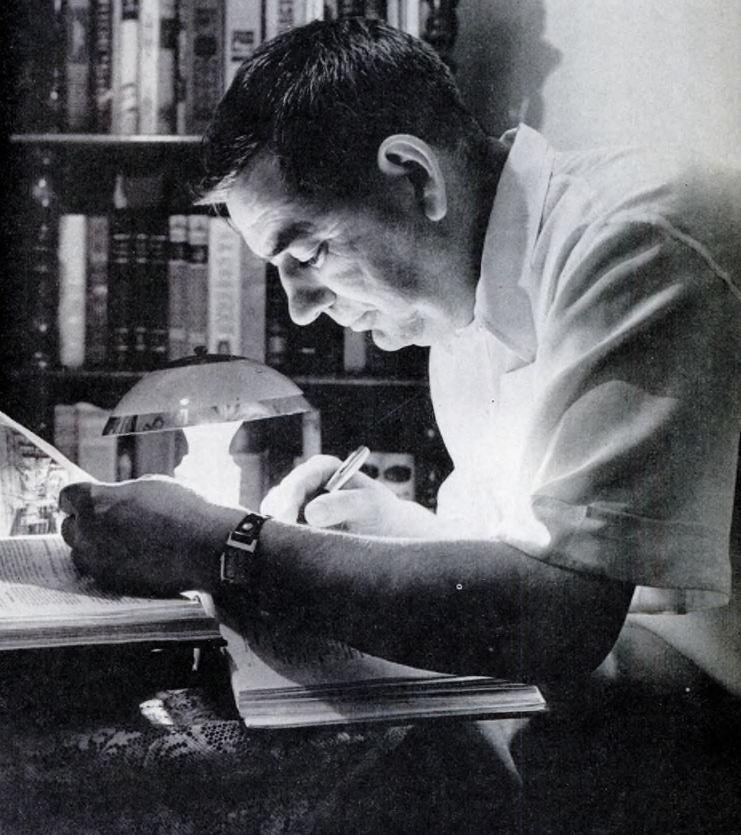

Ivan's big problem then was cooks . There weren't any available, so he trained his own. One of the students Ivan taught in that little cafeteria in Beketovka, Matryona Lavrova, has been working with him ever since. Now she's a first class cook in her own right.

Tasty Menus

Abroskin's cafeteria services the Petrov Plant workers and their families. A three course dinner runs five to seven rubles. The bill of fare, changed daily, offers five or six soups and broths, ten to a dozen entrees and several choices of dessert. Typical dishes are chicken broth, borshch, steak, chicken with rice, fish, pudding, stewed fruit, ice cream .

Abroskin follows the likes and dislikes of his customers very closely. He recently set up a special baked goods department when he noticed a steady demand for pancakes and vareniki (curd or fruit dumplings ). Now tasty meat pies, patties, cakes and doughnuts are available all the time.

Ivan likes to quote the statement of Pavlov. The famous physiologist said that to eat normally and healthfully means to eat with appetite and pleasure. That, says Abroskin, is the motto he cooks by.

The food in his cafeteria is so appetizing that many workers prefer to serve his dishes at home instead of doing their own cooking. These ready-prepared dinners are packed in vacuum flasks and other heat-conserving vessels and are sold at ten per cent less than dinners eaten at the cafeteria. Besides these prepared dinners, the cafeteria sells about twenty different kinds of half-ready items, from dehydrated soups to chops and steaks that take very little time to prepare.

Abroskin's cafeteria also caters for birthdays, weddings and other such festive occasions and will prepare special menus on request. A section of the cafeteria, incidentally, is reserved for those on special diets prescribed by physicians.

Besides being a top quality chef Abroskin does some inventing on the side. He recently worked out a device with a revolving drum which scales fish in a matter of seconds. This is one of his many ingenious gadgets to lighten kitchen chores.

Abroskin has won honors for his culinary skill . In 1954 the Ministry of Trade awarded him the title "Master Cook" - the highest citation in the public catering trades. Besides the hono, the award meant a substantial increase in wages. He was also appointed a member of the Culinary Council. This council, responsible to the Ministry of Trade of the Russian Federation, studies and publicizes the best practices in public catering.

Abroskin lectures and gives demonstrations at the Stalingrad School of Culinary Apprenticeship where young secondary school graduates get a two-year course to qualify as chefs. Many of Abroskin's former students now work in restaurants and cafeterias in Stalingrad and other cities of the country.

Quality Food and Service

The Petrov Plant cafeteria is supervised by the City Soviet. More directly, a committee of the trade union at the plant, the Public Catering Control Committee made up of thirty or so workers at the plant, sees to it that the cafeteria's food and service is up to par.

This is general practice in all commercial and industrial enterprises. There are about 3,000 of these voluntary public inspectors who check on cafeterias and restaurants in Stalingrad. They have a good deal of authority and a complaint from an inspector as to quality of food or service will ordinarily bring speedy remedy. On occasion, as happened recently with Valentina Yeliseyeva who worked in one of the factory cafeterias in Stalingrad, a cook will be discharged on the complaint of a public inspector.

All food establishments are inspected regularly by physicians and food is tested to see that it measures up to the required standard of quality and caloric value.

There are some 600 restaurants of various kinds in Stalingrad, patronized by a third of the city's 600,000 population. The daily turn over is in the neighborhood of a million rubles. Another 250 restaurants are soon to be opened as part of the plan to increase the number of public catering establishments. Nationally more than 64,000 cafeterias, coffee houses and restaurants will be added within the next half-dozen years to the present 127,000 which cater to some 37 million people. Scheduled too are further reductions in prices.

In the very near future these restaurants will be supplied with half-prepared dishes instead of the raw ingredients, shipped from central mechanized factories which will prepare food on a large scale. A factory of this kind is now being built in Stalingrad. Says Abroskin: "I'm all for the idea. First, it cuts down on labor in the kitchen; second, it's a better guarantee of top-quality food and cooking; third, with lower overhead, we'll be able to reduce our prices again.

Comments